[ad_1]

The name Charles Beaumont should be instantly recognizable to any die-hard fan of The Twilight Zone (classic episodes air regularly on SYFY).

After all, Beaumont is credited with writing some of the anthology’s most famous — and often provocative — episodes: “Perchance to Dream,” “Long Live Walter Jameson,” “A Nice Place to Visit,” “Long Distance Call,” “Shadowplay,” “The Howling Man,” “Living Doll,” and this nearly-lost gem starring a young Robert Duvall. Indeed, Beaumont, who adapted several of his own short stories for the show, is considered one of Twilight Zone‘s most consistent writers alongside Richard Matheson and creator/host Rod Serling.

While he received nearly two dozen writing credits throughout the show’s five-season run between 1959 and 1964, Beaumont actually received a little — and sometimes a lot — of creative help from uncredited ghostwriters on numerous episodes.

Why several Twilight Zone episodes were written by uncredited ghostwriters

According to Marc Scott Zicree’s The Twilight Zone Companion, Beaumont was not a well man, health-wise, even in the best of times. “He was always thin,” his friend, the late William F. Nolan. explains in the book. “He almost always had a headache. He used Bromo [a popular pain reliever at the time] like somebody would use water. He had his Bromo bottle with him all the time. He’d buy it in those giant sizes, what he called ‘window sizes,’ and he’d empty one of those a month.”

Such a precarious state of health, coupled with dozens upon dozens of script-related responsibilities, meant that Beaumont could not always meet deadlines, which meant he sometimes required the help of an uncredited ghostwriter. For instance, “Dead Man’s Shoes,” a Season 3 tale of supernatural footwear, was credited to Beaumont, but written by Ocee Rich. Meanwhile, Jerry Sohl, a regular scribe on another anthology, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, took on writing duties for “Living Doll” and the hour-long “The New Exhibit.”

All of this was done in direct violation of WGA rules, with the profits split evenly between Beaumont and his proxy. Sohl states in The Twilight Zone Companion that while he didn’t receive any pension or health insurance remuneration from this under-the-table arrangement, the creative opportunity — one that meant he could completely bypass producer interference — was too juicy to pass up: “I didn’t have to do anything but write. What more could you ask? [Charles] was the one who went in and fought battles.”

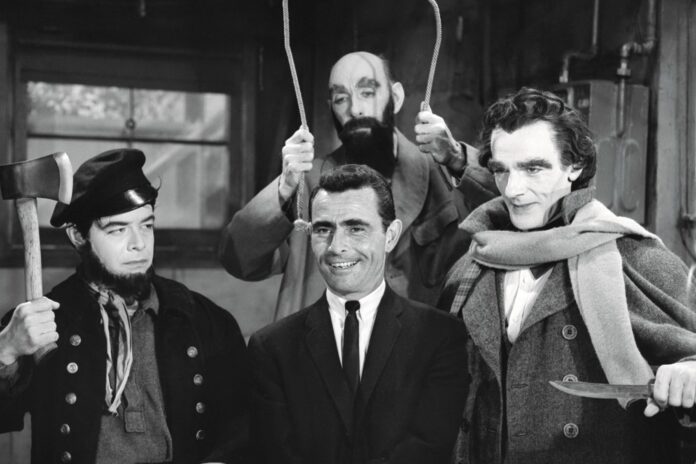

Even better was the fact that most of his teleplays required almost no revisions before filming. “They went right in, and the reason is that Chuck Beaumont scripts were always so great that they didn’t have to do anything,” Sohl adds. Nevertheless, the reality of the uneven situation really hit home for Sohl on the set of “The New Exhibit,” which stars Martin Balsam as a neurotic — and, as it turns out, insane (very fitting, given his role in Psycho a few years earlier) — curator of wax figures modeled after notorious murderers. “Here I am standing with Chuck Beaumont, and John Brahm, the director, comes up, puts his arm around him with the script that I did and says, ‘Chuck, you’ve done it again!’ And here I am, standing right next to Chucky, unable to say a word.'”

As time went on, Beaumont began to drink heavily and, even more alarmingly, appeared to be wasting away — both physically and mentally — despite numerous attempts on the part of his family to find a solution. “I didn’t understand what was happening,” admits Douglas Heyes, director of nine Twilight Zone episodes, including “Eye of the Beholder” and “The Howling Man,” in The Twilight Zone Companion. “Every time I’d see him, he’d seem so much older than I knew he was. I’d say, ‘God, Chuck has aged a lot!'”

It almost seemed as though the talented writer was suffering from the rapid aging experienced by his own Twilight Zone character, the immortal history teacher Walter Jameson (Kevin McCarthy), at the end of Season 1’s “Long Live Walter Jameson. “He just dusted away,” Nolan emphasizes in the book, while drawing the macabre comparison. After a number of tests at UCLA, it was determined that Beaumont had some kind of degenerative neurological disorder — either Alzheimer’s or Pick’s disease.

“Charles Beaumont was dying of pre-senile dementia for the last year-and-a-half of Twilight Zone,” Zicree tells SYFY WIRE over Zoom. “And so, his friends were ghostwriting those scripts … these were great secrets that people entrusted to me to reveal for the first time [in my book].”

After years of what must have been a waking agony, Beaumont passed away at the age of 38 on February 22, 1967. It was the epitome of tragic, a bright and one-of-a-kind imagination snuffed out long before it should have been. “When he died,” his son Chris recalls in Zicree’s book, “he was physically a 95-year-old man and looked 95 and was, in fact, 95 by every calendar except the one on your watch.”

The Twilight Zone airs regularly on SYFY, check out the official schedule for details.

[ad_2]

Source link